Limited research misses the point, again

25th October 2019

In a recent report a research team focus on field scale and forget the rest of the supply network.

In the 25 October issue of the Farmers Weekly journalist Johann Tasker’s article, “Switch to organic farming ‘would increase greenhouse gas’” highlighted findings in the recent research published in the journal Nature Communications, “The greenhouse gas impacts of converting food production in England and Wales to organic methods”.

OF&G (Organic Farmers & Growers) is disappointed with the research conclusions that state moving to organic would increase greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by off-shoring our food production due to lower yields.

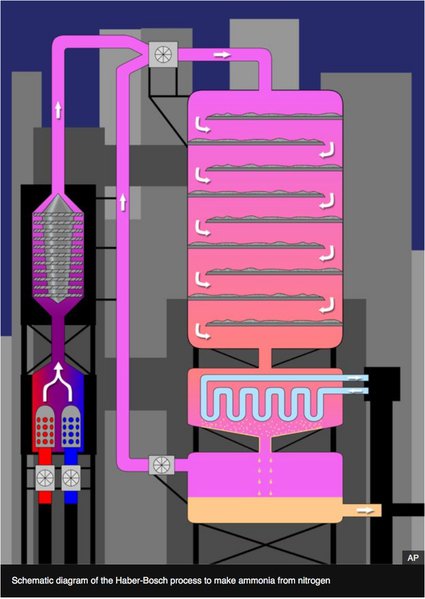

The research appears to fail in several critical areas. Firstly, it fails to recognise the impact on GHG emissions from the manufacture of external agricultural inputs. A recent study by Sheffield University[1] showed ammonium nitrate fertiliser alone used in wheat cultivation contributes to almost half (43%) of the GHG emissions associated with industrial bread production – dwarfing all other processes in the entire supply chain.

The percentage reduction in yield in organic systems cited in the research is also arguable, however, research undertaken by FiBL[2] states that while organic may have lower yields, it represents part of a sustainable solution.

The research also fails to address significant structural issues in our current food system. It’s suggested around 30% of food produced in the UK is wasted and around 40% of the world’s cereal production goes to feeding livestock in intensive systems. 30% of the US cereal crop alone currently goes into biofuel production.

It’s a sobering thought that while 820 million people on the planet don’t have enough to eat, 2,100 million are overweight or obese according to the UN. If we reduced waste and focused on feeding people nutritious diets and not feeding cars or livestock, organic production could feed the world.

In the face of these statistics to simply dismiss organic on the grounds that it can’t fulfil the needs of a dysfunctional food system seem perverse. It seems, therefore, we need a new approach to defining productivity and efficiency - one which allows the benefits of a joined-up system approach.

OF&G recently argued for this in a report[3] proposing a rethink of our definition of productivity and efficiency so that externalities are recognised in a balance sheet approach. Done this way, there’s every reason to believe an organic system is both efficient and productive, with significant benefits of cleaner air and water, and improved biodiversity.

The research in Nature Communications doesn’t recognise that the general farming approach over the last 50 or 60 years has led to impoverished soils and contributed toward a significant reduction in biodiversity. In the UK, there’s been a 56% decline in farmland birds since 1970 and it’s suggested there’s now only 100 harvests left in our soils.

Although the research recognises the benefits an organic system brings to soils and biodiversity, it fails to take a joined-up approach, which has proved to be great fodder for the advocates of ‘business as usual’ - something the IPCC and the UN has agreed is no longer an option.

[1] https://www.farminguk.com/news/researchers-calculate-environmental-impact-of-a-loaf-of-bread_46353.html

[2] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-01410-w

[3] https://ofgorganic.org/news/productivity-and-efficiency-a-new-perspective